Interview: Sir Ian McKellen Part I

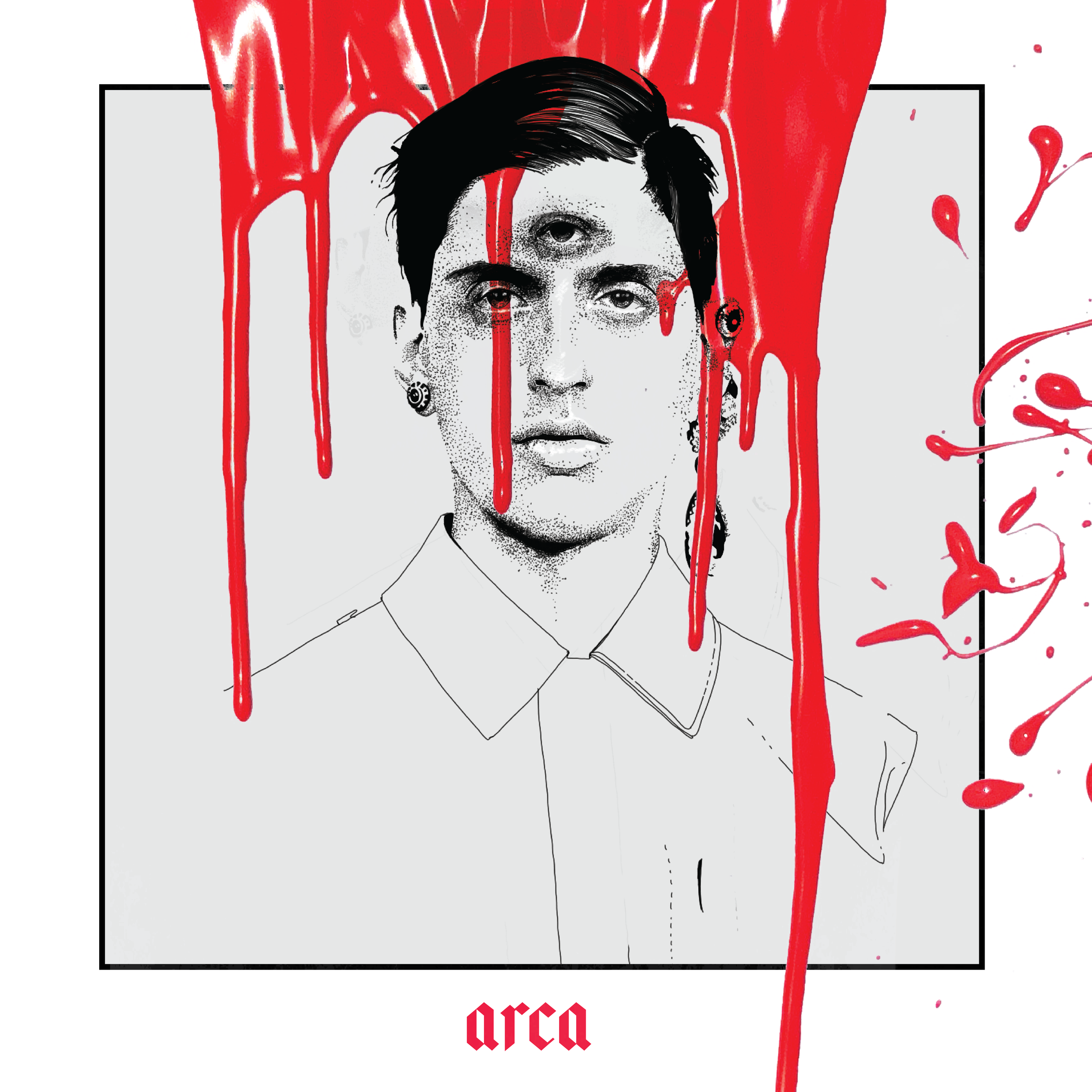

Illustration by Fernando Monroy

An email appears. Almost out of the blue. It's from Sir Ian McKellen. We'd met a year before and I'd mentioned this website I was creating. A few days ago, we'd bumped into each other at the theatre. And now, a casual breezy email from a living legend arrives: Would I like to come to his house and interview him for The Queer Bible? Is tomorrow ok? It isn't, because tomorrow I'll still be having a panic attack screaming, 'SIR IAN MCKELLEN JUST EMAILED ME!' But I say, it's fine, and in a mere twenty-four hours I am sitting in Sir Ian's home. We discuss, among other things, being one of the most revered Shakespearean actors of all time, 'coming out' live on the radio, the formation of LGBTQ+ charity Stonewall, and starring in blockbuster films as iconic characters like Gandalf and Magneto. I was so nervous to visit him I forgot to bring my carefully prepared questions. I needn't have worried. The conversation flowed effortlessly as he led me through his fascinating life and career. As I worked my way through the croissants I'd bought (what does Gandalf eat for breakfast?), Sir Ian chatted away, occasionally chuffing on a rollie. It was a dream.

Here is the unedited first part of our conversation. Enjoy!

Jack: So first of all I wanted to talk about The York Realist gala at the Donmar Warehouse, in aid of the Albert Kennedy Trust charity?

Ian: Well I’m not very good on dates but I think the magic year for me was 1988 when I was 47 years old and I was a party to starting Stonewall, which was a reaction to Section 28, this bad law that the Thatcher government introduced to inhibit schools from talking positively about homosexuality, on the grounds that they would be promoting homosexuality. I took that very personally and a debate came out on the radio. Then I was immediately thrust into gay politics.

Jack: So did you come out on the radio?

Ian: Yeah.

Jack: What were the words that you used?

Ian: I don’t know but you can hear it on…yes. I think I probably said that I’m a homosexual, mispronouncing the word. It’s hommo-sexual, did you know that?

Jack: Why is it ‘hommo'?

Ian: ‘Homo’ is the latin.

Jack: Like ‘homo sapien'?

Ian: Meaning ‘man’. ‘Hommo' is the Greek, meaning ‘the same’. We are the same sex, not…

Jack: So we’re not man-sexuals?

Ian: It’s nothing to do with man.

Jack: Well, it’s a lot to do with man.

Ian: Not if you’re a woman! Hommo-sexual, not homo-sexual.

Jack: Everyone’s gonna think I’m really affected if I start calling it hommo-sexual.

Ian: No, you are being correct. It’s good to know where these words come from. Anyway it’s confusing if a woman is homosexual.

Jack: You’re right, it’s confusing.

Ian: So my friend Michael Cashman and I were going on a similar journey. He was an actor at the time and we both came out together. We were very useful on marches and stuff. We went up to Manchester, I think this was 1988, to an anti Section 28 march, which was one of the great days. Manchester’s always been more radical than other cities.

Jack: Why?

Ian: I don’t know. Bloody-minded Lancastrians…the trade union movement was started in Manchester, all sorts of things. Canal Street was a sort of beacon really, for a time in England. Anyway there we go, we go marching through the streets and we’re being cheered along. Then typical of Manchester, we’re invited into the city hall by the mayor. You couldn’t get anybody in England at that time in a position of authority to be friendly towards gay people, let alone officially friendly. So we’re in there and we meet a little of group of…mainly women but some of their husbands, who were starting this Albert Kennedy Trust. So I know Stonewall and Albert Kennedy Trust are exactly the same year old. That was because Albert…look, that’s a drawing by him, it’s a print.

Jack: It looks like a Picasso?

Ian: That’s done by Albert Kennedy.

Jack: It’s beautiful.

Ian: He was I think thrown out by his parents when he said he was gay. He was on the streets and on the game and certainly on drugs and god knows what. Not happy at all, I think he was 16. One night he was chased by some thugs up to the top of a multi storey car park and he threw himself off. And in his memory this group of perfectly ordinary Mancunian straight men and women saw it immediately and said we must stop this sort of thing happening again. It’s unbelievable. Last year in London there were 250 homeless gay teenagers... 250.

Jack: So these are kids?

Ian: Thrown out by their parents. No friends, no resources like the one you’re doing. Desperate, on their own and you know, there’s no more lonely than the big city where you don’t know anybody.

Jack: And dangerous as well.

Ian: Dangerous. So what they do, I’m not sure how they do it, if such a kid contacts the Albert Kennedy Trust they’ll immediately, without judgement, accept their story. They’ll try and reconcile them to their families, but if that’s not possible then they’ll mentor, provide accommodation for, shelter…they might even foster in some cases and see them through. They’ve a fabulous track record of people who’ve gone to the bar, emerged… Anyway 250 in London last year, 150 in Manchester. They’ve just started working in Newcastle. There were 100 homeless gay teenagers in Newcastle. Nobody has any idea about Glasgow or Edinburgh or Portsmouth or Swansea or Brighton or Birmingham or Coventry because they don’t have the resources. So the little sums that they raise at events like the Donmar...

Jack: They really help? One of the reasons why I started the Queer Bible is when you realise you’re gay, you’re instantly at odds with everyone around you, or you feel 'other' from everyone around you. I think that led me to feel very alone, very self-destructive. Part of what I’m doing is connecting young people up to their amazing history. I want them to know that they’re not just, not alone, but that they walk in the footsteps of some of the greatest human beings to ever walk the face of the planet.

Ian: There you go. Growing up gay at a time when it was illegal to have sex for a man…it’s never been illegal for girls to have sex. There’s never been a single anti-lesbian law in this country. Because I think the men who passed the laws couldn’t possibly imagine it. A lot of straight porn is about two women waiting for a man to join in. That’s what they think.

Jack: But you know a lot of kids today don’t know or believe it was illegal to be gay in this country.

Ian: I go and talk to schools and their jaws literally drop. They think I’ve got it wrong. The one positive about growing up gay and feeling I was on my own is thinking I was a bit special. Now being different…and queer, that was the word used against us, not gay. Gay was invented by some activist somewhere. Weren’t they clever?

Jack: A rebrand!

Ian: Yes, what shall we call ourselves? 'Good As You.'

Jack: Is that what it stood for?

Ian: Well some people think so.

Jack: 'Queer' was other, negative, strange, different…

Ian: Perverted, dangerous. Don’t understand it. Odd. Which is how kids today use the word 'gay', 'This watch is so gay.' So anyway…what I felt about it was, not knowing anybody, my best friend at school was gay. I didn’t know. He didn’t know I was gay. My best friend David Hargreaves. He went on to become director of education at Cambridge University… Professor rather.

Jack: That’s like a Shakespearean tragedy. So you were both going through it separately?

Ian: Yes but you thought that was your destiny. You were queer, you were different, you were…there was a little bit of me that thought ‘oh so, I’m a bit special am I?’ That’s the positive side of being different. But to latch onto that you’d be helping people think that, ‘yeah you are different, but it’s alright, it’s a good thing’.

Jack: The bit that was different about you was the bit that connected to drama, that got a scholarship to Cambridge.

Ian: Well, I escaped you see.

Jack: Do you think part of that was because you were gay and different?

Ian: I think that was an impetus I didn’t know about. A) to leave home, because you should do I think, but then arriving at Cambridge to discover there were other people… we didn’t call ourselves queer, we called ourselves camp. ‘Is he camp?’

Jack: So camp literally meant gay?

Ian: Well, for our little group it did.

Jack: So did you found a community of other camp men at Cambridge?

Ian: No, no…we were all closeted. We weren’t out. Derek Jacobi… no! There were lots and lots of us. Miriam Margoles. None of us said we were anything. Then I fell in love at Cambridge with an American boy who was at RADA and I was in a play with him at Cambridge.

Jack: Do you remember what play?

Ian: Well we did two plays. We did The Lark which was a play about Joan of Arc by Jean Anouilh, and then we did Caesar and Cleopatra by Bernard Shaw. This is all on my website, there’s some pictures… beautiful Kurt. So I had sex for the first time... Oh, I see! This is where it had all been leading. But still a major reason for me becoming a professional actor was because I’d heard you could meet gay people. Where else could you go? There were no clubs in Bolton, no bars. There’s no literature, no internet. There’s nothing on the telly, nothing on the radio. No gay plays, no gay people. Noel Coward… he wasn’t going around saying he was gay, on the contrary. So you were on your own. Then you met somebody else. I thought, if I could get to the theatre… and there were gay people in the theatre and nobody minded. The theatre was a wonderful place. Nobody cares as far as I can see. A few people did but most absolutely accepted whatever… if you were cheating on your partner on a tour, if you were having a weekend with somebody. There’d be gossip but no judgement. If it was two boys or two girls well then…

Jack: That’s even better gossip.

Sir Ian and Dame Judy Dench in Macbeth

Ian: Then I found I could live openly as a gay person without ever mentioning it. That was possible. So I had a longterm relationship when I came to London for the first time. I knew other gay people, we went out together. But we never held hands.

Jack: I don’t hold hands with my partner now in London.

Ian: It’s a strain for me to do that, to kiss someone. If I’m on the tube and a gay friend’s getting off the tube I think, ooh I want them to give me a big kiss and then I’m left sitting there on my own.

Jack: That’s the thing, if you kiss someone and then leave them on the tube, you’re like, bye! Enjoy all the judgmental looks on the tube. But that’s the shame?

Ian: I am not a pioneer, I’ve just gone along and taken advantage of the changes that have happened until we got involved with Stonewall and then we were doing it with a group and then you could get militant a bit more.

Jack: When you did decide to come out, I think Armistead Maupin said…

Ian: I was living with Sean [ director and actor Sean Mathias ] here… I think I wanted to come out, I can’t remember for certain. But it would be my instinct when I was aware of other people coming out, mainly in America. But because I was living with Sean and Sean didn’t like (I didn’t like it either) that he was defined by being my boyfriend… if I’d come out then he would’ve come out and that relationship would’ve been even more oppressive for him. So it was only when we split up that I was free to do whatever I wanted. That I began to actually think about it. Not obsessively. Then I was in America, this was ’87 or something, I met Armistead in San Fransisco. Now Armistead used to 'out' people. He outed Rock Hudson when Rock Hudson was dying, because he was one of Rock’s casual boyfriends. So he was quite militant that people in the public eye who were happily gay had the duty to say that. Because of the effect it would have on other people. So when I said to Armistead and his partner Terry, ‘do you think I should come out?’ It was late at night and well under the influence… he said ‘yes!’ Now I think he would’ve the said the main reason for coming out is that you’re going to feel better about yourself but if you’re in the public eye there’s also a wonderful knock on effect that people see it, note it and then apply it to themselves. So I was ready to come out. Then when I came back to England they were just starting up Section 28 so…I’m not sure whether I went into that broadcast thinking, I’ll come out, but… now ‘come out’… everybody knew I was gay. That’s why I wasn’t oppressed.

Jack: But there are layers of coming out aren’t there?

Ian: Of course there are, and it’s a constant journey. It never stops.

Jack: Every time you go somewhere you often have to come out again and again and again.

Ian: I was coming back in a black cab at three in the morning and… [imitates voice] ‘hello Ian! I was meant to ask you, have you got any grandchildren?’ I thought, Jesus Christ, do I have to start this? Is he going to throw me out if I start telling him I’m gay. No Ian, you’ve gotta come out again. ‘No no no’ I said, ‘I don’t have any children either because I’m gay and when I was growing up you couldn’t get married, you couldn’t have children,' ‘Oh’ he said, ‘I’m gay too’. It’s a good little story that. I was absolutely wrong. I assumed he was straight. He just wanted to chat with another gay man at three o’ clock in the morning.

Jack: That’s a story as old as time!

Ian: So the two areas of my life where I wasn’t out was with the media… I dodged every question, and there were very few of them. I don’t suppose more than half a dozen times in all the interviews I gave did any journalist say ‘are you gay?’ Because it was the worst thing you could possibly say. Simon Callow who was out before me, he was the first actor to be openly gay in this country, he came out… he was never in. He’d been through university and when he started acting he was just going to be open about it. He said in every interview he was gay…they wouldn’t publish it. Because they knew it was the worst thing you could say about somebody, that they were gay. So there was never any pressure.

Jack: No people weren’t begging you to do it, they were trying to cover it up.

Ian: There would be part of the press looking for scandal but I wasn’t…

Jack: You weren’t scandalous.

Ian: No, I was terribly ordinary. But the other part of my life where I was in, where I was closeted, was with all my family. My stepmother - my parents were both dead - my stepmother, my sister. So I had to have a quick runaround, there was two days before they broadcast this… I got two days to tell the family. They all said, ‘Well we’ve always known that Ian. We were baffled as to why you didn’t want to talk about it.'

Jack: So were they being respectful in not talking to you about it? Were they waiting for your lead?

Ian: Yeah they took on the assumption that it was something to be discreet about. Not ashamed but discreet. So my relationships with my family improved overnight because I’d been honest. So that was my coming out. But I tell the kids that coming out… you never stop it. It starts by coming out to yourself.

Jack: So do you think your relationships with your family improved and deepened after you came out to them?

Ian: I became a better son, I became a better brother, I became a better uncle.

Jack: And in your career?

Ian: I became a better actor.

Jack: Why was that do you think?

Ian: Well, because I’d totally changed. Crudely, up till that point my acting was about disguise. You don’t get to see the real Ian McKellen, he’s throwing himself into the part. Then when I was out my acting came about the truth and revelation and not being disguised. So anybody who knew me and after would say ‘overnight, he became a better actor’. Richard Ayre said that, Sean said it. I wasn’t really aware of it. I was a very shy person. At a party I was the one sitting at the skirting board longing for it to be over. Because don’t ask me to be myself, I can’t. Then if you define yourself, how can you not be more confident? Then if you’re more confident you’re going to be better at everything, including acting.

To be continued...

Sir Ian as King Lear

Fernando Monroy is a Mexican illustrator currently studying in México city. His work references pop culture, reflecting the work of photographers, designers and fashion. Out Magazine named him one of twenty young queer artists to watch.